Grief is an all-encompassing emotion. It’s something we all experience, regardless of where we’ve come from or what we’ve been through. Grief affects us all, and as humans who form close relationships with others, it is difficult to avoid.

Whether it’s scans of the brain regions that process grief or measures of the stress hormone cortisol, which is released in grief, studies of grieving brains show no differences based on race, age, or religion. People from all cultures mourn; we all experience sorrow, loss, and despair. We simply do it – and demonstrate it – in various ways.

Averill, a psychology professor in the United States, has compared this to sexual feelings, which, like grief, are biologically driven but expressed in vastly different social contexts.

Sponsered3

Here are a few examples of how grief and mourning can look very different depending on where you live and where you come from.

1. Collective grief is common

When it comes to bereavement in the West, the emphasis is frequently placed on the individual. People talk about their personal grief, and counselling is usually arranged for just one person; even support groups have individual members. However, the family – or, for many Indigenous people, the tribe – grieves collectively, and this is more pronounced in some cultures than others.

Sponsered3

In Hindu families in India, for example, relatives and friends gather in an elaborate 13-day ritual to support the immediate family. A widow’s position as head of the household is taken over by the wife of her oldest son.

The Lakota tribe elders use the phrase “mitakuye oyasin,” which means “we are all related,” which is typical of Native American culture. Everyone in the tribe mourns the death of a member.

The Buddhist mourning period after a funeral lasts 49 days in Tibet. During this time, the family gathers to make clay figures and prayer flags, allowing them to express their grief collectively.

Sponsered3

Collective grief is also the norm in traditional Chinese culture, but the family also makes collective decisions, which sometimes exclude the dying person. This was depicted in the 2019 film The Farewell, which was based on the life of director and writer Lulu Wong. In the film, a Chinese family discovers that their grandmother has only a few months to live and decides to keep her in the dark, planning a wedding to gather before she dies.

2. Grieving times vary by culture

After a bereavement, a steady return to normal functioning can typically take two or more years. Experts no longer talk of “moving on”, but instead see grief as a way of adapting to loss while forming a continuing bond with the lost loved one. But again, this varies from culture to culture.

Sponsered3

In Bali, Indonesia, mourning is brief and tearfulness is discouraged. If family members do cry, tears must not fall on the body as this is thought to give the person a bad place in heaven. To cry for too long is thought to invoke malevolent spirits and encumber the dead person’s soul with unhappiness.

In Egypt, tearfully grieving after seven years would still be seen as healthy and normal – whereas in the US this would be considered a disorder. Indeed, in the west, intense grief exceeding 12 months is labelled “prolonged grief disorder”.

3. People like to visit the body

Sponsered3

The way people interact with the dead body also differs culturally. For example, between the death and the funeral, the Toraja people on the island of Sulawesi, Indonesia, treat their relative as if they were ill rather than dead, by bringing them food and keeping them company.

Europe has its own set of rules regarding customs. Until the mid-twentieth century, the lying-out of the body was done by village women along the Yorkshire coast. Friends and family would come to pay their respects and recall memories of the deceased. This practice is still practiced in some countries.

In Italy, for example, a temporary refrigerated coffin is delivered to the family home so that people can bring flowers and pay their respects right away.

Sponsered3

4. Signs from above

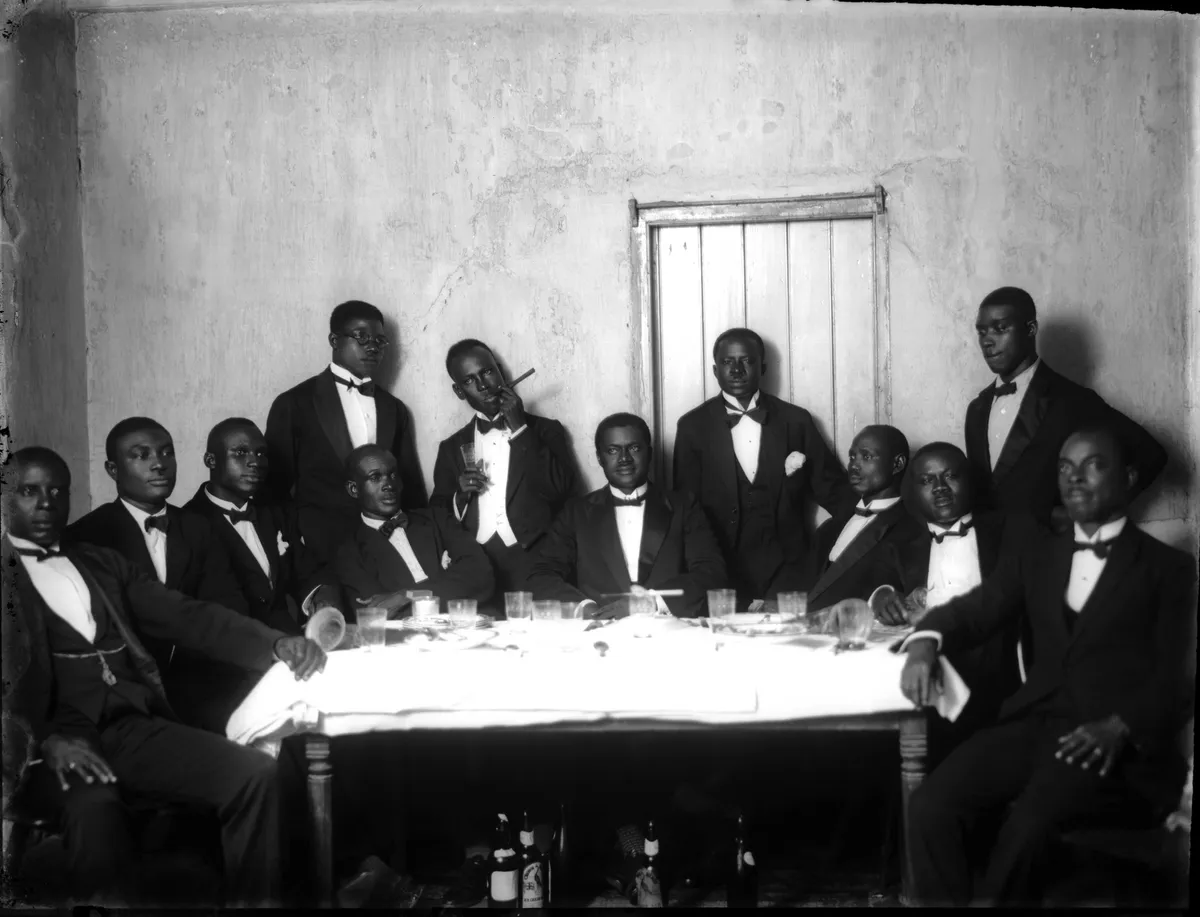

Some people in the United Kingdom believe that white feathers are a message from heaven, but this is often dismissed as childish magical thinking. However, spiritual connection to the deceased is considered normal and very real in many African societies.

Traditional belief in Sub-Saharan Africa is that the dead become spirits but remain in the living world on Earth. They are known as the living dead. In dreams, the spirit may appear in human form.

Sponsered3

5. Sending on the spirit

The indigenous Mori people of New Zealand set aside time to grieve and mourn. Tangihanga is a process in which they perform rites for the dead. After rituals send the spirit on its way, the body is prepared by an undertaker, who is often assisted by family members. The body is returned to the family home for reminiscence and celebration.

Elaborate rituals, including dances and songs, are then performed, followed by a farewell speech. Traditional artifacts such as clothing, weapons, and jewelry are on display. Following the funeral, there is a ritual cleansing and feasting of the deceased’s home, followed by the unveiling of the headstone.

Sponsered3

Sponsered3